Clockmaking: A lost industry of Congleton

Author: Ian Doughty

Congleton Museum has in its collection a longcase clock made by John Whitehurst the elder of Congleton. What might it tell us about 18th century Congleton?

Congleton’s clockmakers were the town’s precision engineers of the 18th and early 19th centuries. They were not only exquisite craftsmen, making the fine and accurate brass components which they assembled to make the intricate clock mechanisms, but also knowledgeable mathematicians able to calculate the exact ratios required between the gears to ensure accurate time keeping. This was achieved through the transfer of the power stored in the descending weight to the rotary motion of the gears, which drove the hands of the clock to tell the time. It is therefore not surprising to find clockmakers like John Whitehurst and Edward Drakeford associated with the town’s growing industries, which were equally dependent upon the transfer of the rotary power generated by waterwheels, through gearing, to drive the silk throwing engines.

One example is the maker of this recently acquired clock, John Whitehurst the elder, who came to the town in 1708 from Biddulph to set up his clockmaking business. He became a prominent citizen, being elected to various offices of Congleton Corporation – ‘Burleyman’ in 1735, ‘Market Looker’ in 1735, ‘Commons Looker’ in 1737 and ‘Inmate Looker’, responsible for the welfare of the poor in the workhouse, in 1738 and 1747.

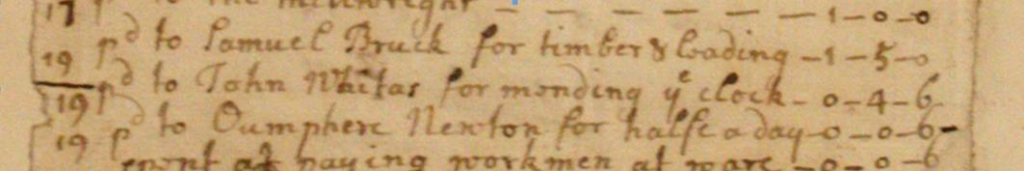

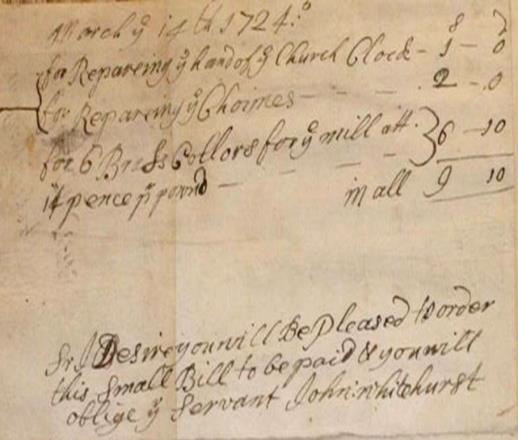

The corporation, for a considerable period of time, entrusted him with the care of the town’s clocks, paying him four shillings and sixpence for ‘mending ye clock’ in 1714 and five shillings ‘for putting ropes to the town clock’ in 1754. It is however, this signed bill of 1724, pinned into the town accounts, which is the most intriguing, as its shows that John Whitehurst’s workshop was not only capable of making high quality clocks, but of manufacturing what we would now understand as industrial machine parts. It requests payment for repairs to the hand of the church clock at one shilling and to the chimes at two shillings, but also payment of six shillings and 10 pence for supplying ‘six brass collors for the mill’ at 14 pence per pound, a total weight of 5½lbs. As it was the only recorded mill in the town at this time these collors must have been for the town’s corn mill.

This account goes some way to explain how craftsmen like John Whitehurst were able to make a living. It is highly unlikely that a town the size Congleton was in 1750, would have had sufficient households with the wealth to purchase ‘luxury items’, such as this clock, over the 50 years John Whitehurst was producing clocks.

The town accounts also reveal a further aspect of John Whitehurst’s commercial interests, for in both 1729 and 1730 he was paid one shilling for ale, suggesting that he was either an innkeeper or brewer as well as a clockmaker.

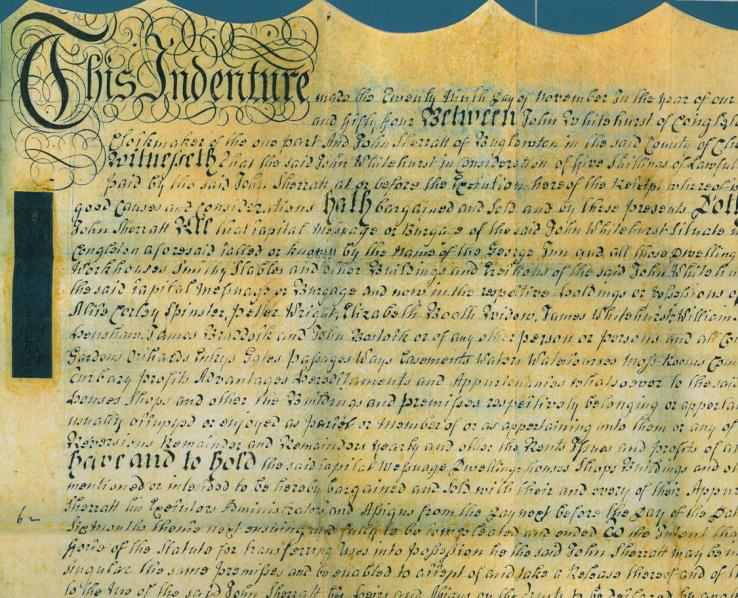

This is confirmed in an indenture dated 29th November 1754, in which John Whitehurst transfers to John Sherratt of Buglawton the ‘capital messuage or burgage of the said John Whitehurst situate in or near the High Street in Congleton, called by the name of the George Inn and all those dwelling houses, edifices, rooms, shops, workhouses, smithy and stables and other buildings adjoining in the possession of John Whitehurst; Alice Corley, spinster; Peter Wright, Elizabeth Booth, widow; James Whitehurst; William Shrigley; John Seaman; Josiah Henshaw; James Braddock and John Bostock.’ This clearly indicates that by 1754 John Whitehurst had amassed a considerable High Street property holding. It is difficult to identify the purpose of this transaction; could it have been that at 67 years of age he had decided to retire and pass the business on to his son James?

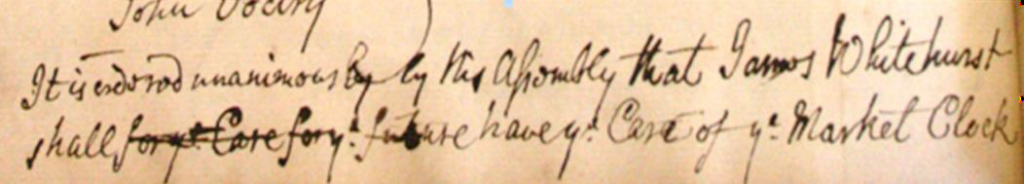

The town accounts suggest this might be so, for in the same year the corporation took the decision to place the future care of the market clock in the hands of James Whitehurst.

It is therefore only proper that the museum should exhibit a clock by a man who was not only one of the town’s earliest recorded clockmakers, but the founder of a clockmaking dynasty. At least three generations of the family continued to work in the town; John himself, his son James and James’ son Egerton, whilst John’s eldest son, also called John, left to establish his own clockmaking business in Derby. The successor business is still in existence today, but now operating under the name of Smith of Derby. It is highly probable that both John and James were apprenticed to their father and the skills exhibited in the making of this clock were passed on to the next generation.

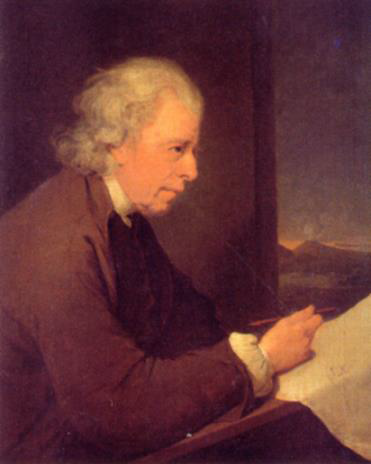

John of Derby not only became a renowned clockmaker, but also a manufacturer of barometers, pyrometers (high temperature thermometers) and orreries (mechanical models of the solar system).

He also published one of the earliest geology books. He was a founder member of the Lunar Society, which included Erasmus Darwin, Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton, James Watt and Joseph Priestly, as well as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

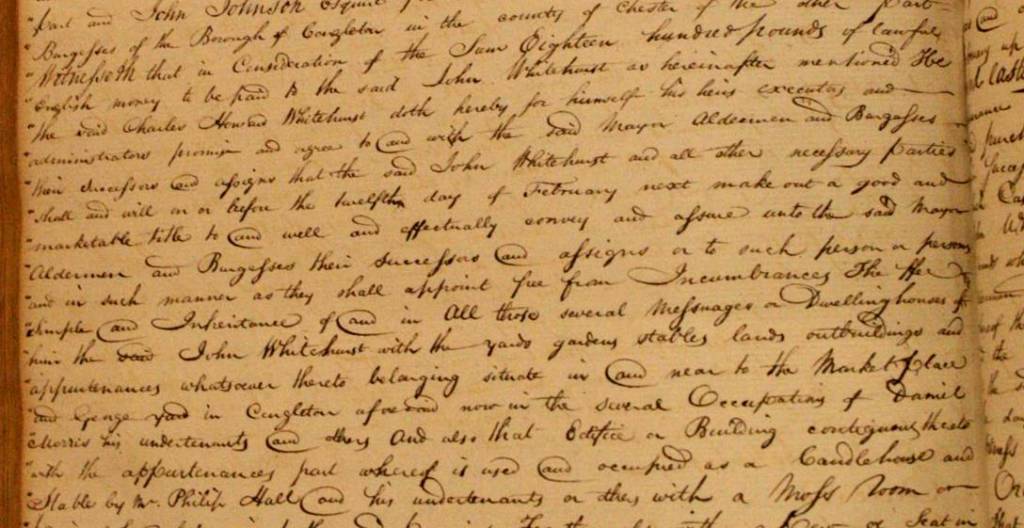

One question remains concerning John Whitehurst the elder: where was the George Inn and his extensive High Street works? Could this entry from one of the town’s order books provide an answer? In 1825 the corporation was intent on increasing its land holdings adjacent to the then town hall in order to extend the butcher’s shambles, and agreed to purchase for £1,800

‘The several messages or dwelling houses of him the said John Whitehurst with the yards gardens stables lands outbuildings and appurtenances whatsoever thereto belonging situate in and near to the Market Place and George Yard in Congleton aforesaid now in the several occupations of Daniel Morris his undertenants and others and also that edifice or building contiguous thereto with the appurtenances part whereof is used and occupied as a candle house and stable by Mr Philip Hall and his under tenants’.

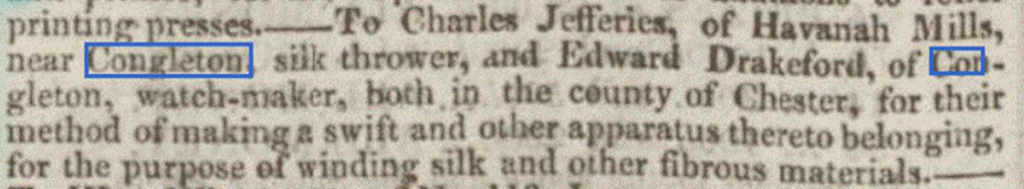

As numbers 7 and 9 High Street have, since 1622, formed part of Dr William Dean’s charitable bequest, the only possible location for Whitehurst’s George Inn could be what is now numbers 11 or 13 High Street or the land behind in behind them in what is now Market Square. Further evidence of this close relationship between a Congleton clockmaker and a local industrialist comes from this extract from the Hereford Journal of 1824, reporting that Edward Drakeford, clockmaker of Congleton, and Charles Jefferies, the owner and operator of the Havannah Mills had been granted a patent for their improvements to the silk winding engine.

Clock manufacture in the late 18th and early 19th century does not appear to have been a minor industry. Between 1750 and 1800 there were thirteen recorded clockmakers operating within the town. One of these, Thomas Foden, the maker of another recently acquired clock, was thought to have operated in the town between 1753 and 1785.

Foden was not an inconsiderable producer of clocks, as his death notice in the Manchester Mercury reported that on his death his stock in trade comprised ‘fifty 8 day and ten 30-hour clock movements.’

The clockmakers of Congleton are a fascinating aspect of the town’s industrial heritage which has long since been neglected and would benefit from further research.